Media Revolution and Propaganda in the Great War

Newsreels, the oldest form of news through motion pictures, established themselves as an influential information and propaganda medium during World War I. Based on the examples of France, the United Kingdom, the German Kaiserreich and the United States, the article sheds light on the development of the production of the new medium during the Great War and on the image it mediates of the war events. A list provides links to newsreel collections covering the war available on the Web.

By Fridolin Furger, December 2018

On July 20, 1916, at 7.30 am, French troops launch an attack from Herleville on German positions at Vermandovillers and the Bois Étoilé. Two cameramen, working for France’s newsreel firms, are accompanying them. Their shots, summed up in L’offensive française sur la Somme, show French soldiers in trenches going over the top and storming in their hundreds into the no man’s land towards the enemy. Other scenes document the response by the German artillery, later on, German soldiers are shown surrendering to the French. The attack is part of the Battle of the Somme which has been raging for three weeks. Intertitles emphasize the success of the attack by providing information on the number of Germans made prisoners and on weapons captured. However, by this point in time, it has long become apparent that this major offensive by British and French troops would end in a debacle.

Scene from the French documentary film L’Offensive française sur la Sommen (Screenshot). Copyright ECPAD.

September 1914. On the Marne, just 60 km from Paris, French and British troops stop the German advance into France by lancing a counteroffensive. In contrast to the Battle of the Somme, the French population doesn’t get to see even a single moving picture of the First Battle of the Marne which marks a turning point in the Great War and the beginning of trench warfare. At this early stage of the war, motion picture teams and still photographers have no access to the country’s troops, let alone to combat zones. The government und military authorities fear that photographs and motion pictures of the war would play into the hands of enemy espionage, and that people’s exposure to the crude reality of the war would weaken the nation’s morale and will to fight. The same reasons prompt armies in Britain, the German Reich, and in other belligerent countries to keep neeswreel companies at a distance from the armed forces.

Camera operators to the battlefronts!

Newsreel producers anywhere protest against the civil and army authorities blocking their cameramen’s access to the troops. «More Camera Operators to the Battle Fronts!», demands a German trade journal. Cinemagoers would not be satisfied with reports covering just the mobilization of soldiers or military exercises. People want to see real and « true » images of the war. At the same time, members of the ruling elites begin to realise that the moving picture is an ideal medium for reaching the masses with propaganda. Furthermore, there are demands that the war should be documented for posterity. Gradually, motion picture cameramen and still photographers get at least limited access to the troops, to varying degrees, depending on the country. Finally, most armies begin to set up their own photographic and film units and to produce official war newsreels and documentary films.

Newsreels were first introduced in French cinemas in 1908. At the beginning oft the Great War, they are common in many European countries and in the United States. Soundless and committed to entertainment, they enjoy little respect as news medium. Technically, their means to cover events are still very limited. Nevertheless, despite the most adverse circumstances, newsreels trigger a real media revolution during the Great War. They establish themselves as a news medium and considerably accelerate the world’s entry into the visual age of the 20th century. For the first time, a major conflict is documented widely by moving pictures. Millions of people watch the events of the war in movie theaters and at other venues. However, newsreels do not provide a coherent presentation of the course of the war. This task is still accommplished by the press alone. What fascinates people about the medium, is the sense of immediacy and nearness it creates with the troops and relatives at the front.

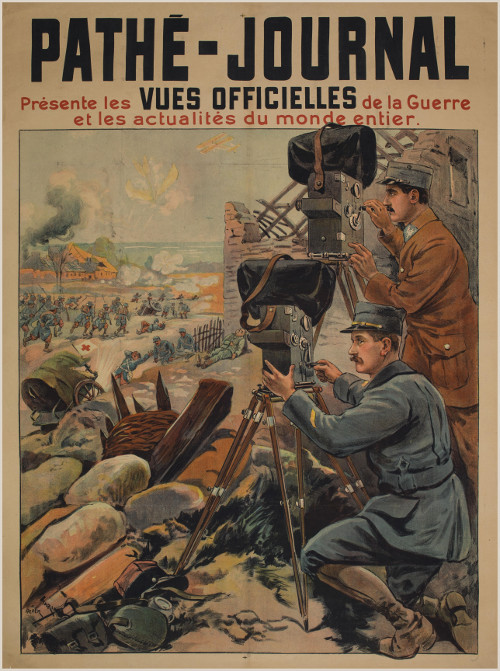

At the beginning of the war, France’s cinema audiences can watch and enjoy newsreels produced by four major film companies: Pathé-Journal, Gaumont-Actualités, Éclair-Journal and Éclipse-Journal. Faced with the film industry’s disapproval of the armed forces keeping the press at a distance, the French army establishes the Section Cinématographique des Armées (SCA) and a photographic unit (SPA) in February 1915. Four cameramen are assigned to the front sectors by turns, at first one of each of the leading companies, later considerably more. The footage is available to all companies involved. Access to the front, however, is handled very restrictively. In January 1917, the army merges both units into the Section Cinématographique et Photographique des Armées (SCPA). From now on, the SCPA ist the only institution authorized to film the troops and produces its own newsreel, Les Annales de la Guerre. Entirely dedicated to the war, this official newsreel is released weekly and is compulsorily shown in all cinemas.

In the United Kingdom, Pathé, Gaumont and the British Topical Budget Company dominate the newsreel market. At the beginning of the war, their film crews are free to follow the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in Belgium and France. In early 1915, cameramen are forbidden from going to the continent. From the end of November of the same year, a consortium of film producers starts to cover events on the Western Front with the War Department’s permission. Among the documentaries the consortium produces, The Battle of the Somme stands out. It causes a stir when film theaters show it in August 1916 and is received with great interest by the film audience.

This encourages the British government to transfer the permission to cover the war to the newly formed War Office Cinematographer Committee (WOCC) at the War Department. The WOCC continues to produce documentary films, but does not supply newsreel companies with footage. In a further step, by an agreement with the Topical Budget Company, and finally with its takeover, the WOCC creates the basis for an official weekly war newsreel. The War Office Official Topical, as it is called, appears from May 1917. In February 1918, the newsreel is renamed Pictorial News (Official).

In August 1914, the German Reich prohibits the import of films from enemy countries and in some cases confiscates foreign production facilities. Emerging domestic companies want to profit from the vacuum created by the elimintation of the main foreign newsreels dominated by French companies. In October 1914, the War Department awards licenses to purely German and patriotic-minded companies. These include in particular Messter-Film and Eiko-Film. These two companies will be the only ones to produce newsreels until the end of the war. Their scope of freedom to cover the events of war, however, remains extremely limited as cameramen get no acess to the front.

Source: Bibliothéque Nationale de France (in public domain).

In mid-1916, the increasing weariness of the war among Germans compels the Ministry of War to reinforce the use of film for propaganda and raising the nation’s mood. Following the French model, the Army sets up the Military Photo and Film Unit (Militärische Foto- und Filmstelle), a centrally organized institution. In January 1917, this unit is replaced by the Bild- und Filmamt (Bufa), which will deploy seven crews (8 according to some sources). Its productions include feature and documentary films, among others Bei unseren Helden an der Somme (With our heroes on the Somme), as a counterpart to the British Somme film. The Bufa does not produce newsreels, but provides private companies with footage.

Patriotism and censorship

What kind of overall picture of World War I do newsreels convey? In all belligerent countries, all news media are subject to strict military control. Newsreel producers are particularly hard hit because they depend on the access to the theaters of war. Government requirements oblige them not to show sensitive areas. Cameramen, mostly army personnel and often with experience in the film industry, are embedded in the troops. Censors decide on multiple levels what part of the footage the public is allowed to see. Footage kept back by censors ends up in archives or is destroyed. However, film producers would hardly take a critical view even without censorship.

Newsreels emphasize the combat effectiveness of one’s own country’s army, the readiness of the troops and the entire nation’s support of the war effort. These messages are evoked through a mix of typical subjects, often patriotically and nationalistically charged. Again and again, endless columns of soldiers can be seen, all types of weapons are presented, and prisoners of war are schowcased. Camera crews cover parades and the awarding of military decorations, they shoot events showing prominent politicians, high-ranking military officers and crowned heads on troop visits. The British and the French frequently present units from the colonies, as for example in Les Spahis algériens en Belgique.

Impressions from the home front underpin the country’s readiness to make sacrifices, often focusing on women who now take the place of men in many areas. Special attention is paid to the armaments industry, impressively staged in the French documentary La Main d’oeuvre féminine dans les usines de guerre. Newsreels are also dedicated to various aspects of every day life during the war. In May 1915, Topical Budget reports on an anti-German rally and attacks on German stores in London. Pictorial News (Official) 345-2, in April 1918, shows a fleet of cinema vehicles used by the government to provide the rural population with the « truth » about the war.

The coverage of war events is largely limited to the domestic perspective, the home front, and the theaters of war, where troops of one’s own country are fighting. Allied nations exchange footage with each other. When Entente and German forces are stalled in trench warfare along the Western Front, moving pictures from distant locations are very well received by the cinema audience. Cameramen follow troops werever these are deployed. A Messter-Woche in 1915 reports on the deployment of German troops in Turkey. Les Annales de la guerre No. 37 documents the transfer of French troops to Italy where they rush to the aid of the ally against Austria-Hungary. In 1917, another edition of the French war newsreel, Les Annales de la guerre No. 27, shows film footage on the Entente offensive in Macedonia where French troops are fighting with Serbs and Greeks against Bulgaria. British cameramen shoot extensively in the Middle East. Occasionally, independent film reporters manage to cover troops in action. For example, in 1916, a Pathé team accompanies Russian troops for some time, documented in With the Russian Army.

For cameramen to report from the front means mainly to document soldiers’ activities in rear positions. Rarely do they get to the foremost lines. The focus is on bringing in supplies, setting up positions and on scenes showing soldiers in trenches. Shots of artillery guns, in combination with camera pans capturing the grenade impact on the horizon, seem particularly attractive. The public hardly ever gets to see the inhuman drudgery in the mud of the battlefields, although footage would be available. Far more agreeable for the reports downplaying the horrors of war are images of soldiers in their spare time, having meals, smoking, or writing letters.

Invisible horror

Combat actions, strictly speaking, and the horrors of trench battles remain invisible. Authorities do not want to confront the the public with the images of seriously injured or mutilated soldiers. When wounded soldiers are shown, they are usually already doctored, or they are receiving help. Reports on sanitary troops demonstrate how well the injured, even the enemy, are cared for. A telling example for this is the Bufa documentary Im Lazarett Assfeld in Sedan. Death in one’s own ranks is hinted at discreetly, for example, using pictures of graves. Corpses of enemy soldiers, however, are at least sporadically shown as in Les Annales de la guerre No. 66. This restraint is not only an expression of respect for the affected relatives. Even in the newsreels’ intertitles, no information ist given as to killed or wounded soldiers, just as setbacks are consistently ignored. This is true even for the above mentioned films on the Battle of the Somme, although more than 20,000 British soldiers were killed on the first day of the battle alone.

Ultimately, the absence of combat scenes is less attributable to censorship than to technology. The big, heavy cameras are operated by crank and require the support by a tripod. Therefore, it is just impossible for cameramen to follow the advancing soldiers. Frequently, the lighting conditions do not allow for filming. Those who shoot at the front take a high risk. On the French side alone, several operators are killed or injured. Not least, cameramen endanger their own troops and therefore are often unwelcome at the front. The difficulty of shooting combat scenes, even in an initial phase, is illustrated by The Battle of the Somme. The famous scene showing soldiers going over the top (begin Part III) has been reenacted. Especially at the beginning of the war, newsreel companies as well often resort to manipulation. They show staged scenes and present footage of military exercises as current coverage.

Screenshot from Mobilizing Movies! the U.S. Signal Corps Goes to War, 1917-1919.

Copyright National Archives (III-SC-25898).

Despite all the embellished coverage of the war, many reports convey without doubt an idea of the horror of the Great War. After the end of battles, cameramen are faced with scenes of devastation, ruins of bombed villages and towns, and apocalyptic landscapes. As can be seen in L’Avance française de Soissons à Reims, the camera captures these scenes in long panning shots. The French and the British use the destructions caused by the enemy to accuse the Germans, contemptuously called « Boches » and « Huns », of cruelty and barbarism. Emphasis is placed on emblematic objects such as cathedrals or churches, pointedly staged in Les Annales de la guerre n°5. The Germans counter these allegations with scenes that prove their human behaviour. For their part, they accuse the French of brutal ruthlessness, even towards their own people. This is expressed sarcastically by the documentary Wie Frankreich das Elsass befreit (How France frees Alsace), released in 1917.

Newsreels, documentaries and feature films are also distributed and marketed abroad, in order to win neutral and friendly countries over to one’s side. To abtain the favor of the United States, the Entente and the Kaiserreich engage in a fierce war of propaganda, which the Germans finally lose. With the aim of persuading President Wilson’s government to give up its neutrality, the Entente puts the Kaiserreich in the pillory, in particular for atrocities committed during the attack on neutral Belgium. In response, to propagate its own side of the war, the German government allows selected American journalists and film reporters to cover events in the Reich and to accompany German troops on the Eastern front. However, to produce convincing film propaganda in the USA, Germans lack professionalism and an understanding of people’s mentality.

US film reporters on Europe’s battlefields

After the entry of the USA into the war, approved by Congress on April 6, 1917, the U.S. Army starts to build a photo and film unit, following the example of France und Britain. At the beginning, the military leadership primarily intends to document the deployment of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) in Europe. The U.S. Army Signal Corps, until now responsible for military intelligence, takes over the task. Their cameramen arrive poorly equipped in Europe, but finally, the Signal Corps will have an imposing crew at its disposal which comprises more than 500 officers and soldiers by the end of the war. Each division and other units are assigned a team. In a short time, the Signal Corps produces a huge amount of footage, focusing on the army’s training in the US, the arrival of troops at French harbors and on front-line operations. As their European counterparts, America’s film operators rarely come up with spectacular shots from the front. This can clearly be observed by watching documentaries on two of the US Army’s most important missions, The St. Mihiel Offensive, and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. For readers who want to know more about the subject, an exciting insight into the work of the Signal Corps is provided by Graham C. Cooper and Ron van Dopperen’s documentary Mobilizing Movies! The U.S. Signal Corps Goes to War, 1917-1919.

Just days after America’s entry into the war, President Wilson calls to life the Committee on Public Information (CPI). This unit forms the basis for an unprecedented propaganda campaign to unify the people behind the war effort. The CPI also acts as censor. The government’s aim is to keep the extent of the intervention secret, and it wants to prevent the recruitment of soldiers from being affected. The CPI is responsible for the use of the footage supplied by the Signal Corps. In September 1917, a Division of Films is founded to use film documents for public relations. At the beginning, the Red Cross manages the distribution and allocation of footage to newsreel companies. Since this proves to be little efficient, the Division of Films takes over the production and distribution of films. In order to gain the widest possible distribution, it uses commercial channels. The CPI produces propagandistically staged films and a war newsreel, the Official War Review, distributed by Pathé. The Official War Review appears from 1 July 1918 in 31 issues. A compilation of the war newsreel, which is difficult to trace in archives, has been created by the National Archives: Official War Review (USA 1918 /1919).

Despite their propaganda function, newsreels provide a complex picture of World War I and remain a treasure trove of inestimable value. They form the basis of innumerable documentary and feature films and continue to shape the memory of the Great War. For a long time, however, access to film documents was difficult. Meanwhile, film collections related to World War I of various institutions are extensively or partially digitized and in part available on the Web. A selection of freely accessible collections on the subject is listed in the appendix of this article, provided with notes and links to the respective websites.

Bibliography – Sources used for this article

Abel, Richard: Charge and Countercharge: “Documentary” War Pictures in the USA. In: Film History, Vol. 22, 2011, pp. 366-388.

Barkhausen, Hans: Filmpropaganda für Deutschland im Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg. Olms Presse, Hildesheim 1982.

Bucher, Peter: Findbücher zu Beständen des Bundesarchivs – Band 8: Wochenschauen und Dokumentarfilme, 1895-1950. Bundesarchiv, Koblenz 1984.

Brownlow, Kevin: The War, The West, and The Wilderness. Secker & Warburg, London 1979.

Castellan, James W. / van Dopperen, Ron / Graham, Cooper C.: American Cinematographers in the Great War, 1914-1918. John Libbey Publishing Ltd, New Barnet, Herts. 2014.

Derenthal, Ludwig / Klamm, Stefanie (Hrsg.): Fotografie im Ersten Weltkrieg. Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. E.A. Seemann Verlag, Leipzig 2014.

Van Dopperen, Ron / Graham, Cooper C.: Film flashes of the European front: The war diary of Albert K. Dawson, 1915-1916. In: Film History, 4.2, 1990, pp. 123-129.

Van Dopperen, Ron: Shooting the Great War. Albert Dawson and the American Correspondent Film Company. In: Film History, Vol 23, 2011, pp. 20-37.

Fielding, Raymond: The American Newsreel. A Complete History, 1911-1067. McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishing, 2nd Ed., Jefferson, NC / London 1972.

Fulwider, Chad R.: Filmpropaganda and Kultur: The German Dilemma, 1914-1917. In: Film & History, 45/2, Winter 2015.

Giuliani, Luca: La grande guerra sul grande schermo – Der Erste Welgkrieg auf der Leinwand – The Great War on the big screen. Fondazione Museo Storico del Trentino, Trento 2015.

Graham, Cooper C.: The Kaiser and the Cameraman: W.H. Durborough on the Eastern Front, 1915. In: Film History, Vol 22, Nr. 1, 2010, pp. 22-40.

Hammond, Michael : The Battle of the Somme (1916): An Industrial Process Film that ‘Wounds the Heart’. In: Hammond, Michael / Williams, Michael: British Silent Cinema and The Great War. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2011.

Huret, Marcel: Ciné Actualités. Histoire de la presse filmée 1895-1980. Henri Veyrier, Paris 1984.

McKernan, Luke: Topical Budget. In: Smither, R. and Klaue, W. (ed.): Newsreels in Film Archives. A Survey. Based on the FIAF Newsreel Symposium. Flicks Books, Trowbridge / Wiltshire 1996.

McKernan, Luke: Propaganda, patriotism and profit: Charles Urban and British official war films in America during the First World War. In: Film History, Vol. 14, 2002, pp. 369-389.

Miihl-Benninghaus, Wolfgang: Newsreel Images of the Military and War, 1914-1918. In: Elsaesser, Thomas (ed.): A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decade, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 1996.

Mould, David: Washington’s War on Film: Government Film Production and Distribution 1917-1918. In: Journal of the University Film Association, Vol. 32, 3, Summer 1980.

Mould, David H.: American Newsfilm 1914-1919. The Underexposed War. Garland Publishing, Inc., New York / London 1983.

Morrissey, Priska: Out of the Shadows: The Impact of the First World War in the Status of Studio Cameramen in France. In: Film History, Vol. 22, 2010, pp. 479-487.

Rather, Rainer: Learning from the Enemy: German Film Propaganda in World War I. In: Elsaesser, Thomas (ed.): A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decade, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 1996.

Smith, Adrian / Hammond, Michael: The Great War and the Moving Image. In: Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Vol 35, No. 4, 2015, pp. 553-558.

Schulze, Sabine, et. al. (Hrsg.). Krieg und Propaganda. Katalog zur Ausstellung im Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, 20. Juni bis 2. November 2014. Hirmer Verlag, München 2014.

Sorlin, Pierre: The French Newsreels of the First World War. In: Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Vol. 24, No. 4, 2004, pp. 507-5015.

Steward, Phillip W.: BATTLEFILM: Motion Pictures of the Great War. In: Prologue. Quarterly Publication of the National Archives. Vol. 40, Nr. 2, Summer 2008.

Steward, Phillip W.: The Reel Story of the Great War. In: Prologue. Quarterly Publication of the National Archives. Vol. 49, Nr. 4, Winter 2017/18.

Véray, Laurent: 1914-1918, the first media war of the twentieth century: The example of French newsreels. In: Film History, Vol. 22, 2010, pp. 408-425.

Voigt, Jürgen: Die Kino-Wochenschau : Medium eines bewegten Jahrhunderts. Edition ARCHAEA, Gelsenkirchen / Schwelm 2014.

Welch, David A.: Cinema and Society in Imperial Germany 1905-1918. In: German History, 8, 1, February 1990.

Zimmermann, Peter (Hrsg.): Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 1, Kaiserreich, 1895-1918, hrsg. von Uli Jung [et al.], Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2005.

APPENDIX

Newsreel collections related to World War I (A selection):

EUROPEAN FILM GATEWAY (EFG) / EUROPEANA:

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the First World War, the European Film Gateway has put together, as part of the EFG1914 project, a wide selection of newsreels, documentaries and feature films related to the conflict. About 30 archives and museums from 19 European countries contributed to this documentation. The film documents are in part linked to the websites of the providers, some of them are available directly on the EFG website.

EUROPEANA:

The motion pictures selected for the EFG1914 project at the European Film Gateway are also available on the Europeana portal – as part of the Europeana 1914-1918 documentation. In addition to film documents, this immense selection includes other media such as letters, postcards and photographs.

IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUMS (IWM):

The newsreels and documentary films produced in Great Britain during World War I under the supervision of the War Department are to a large extent preserved and archived at the Imperial War Museums (IWM), founded in 1917. A wide selection of Topical Budget, War Official Topical Budget and Pictorial News (Official) newsreel issues are available online. The IWM also holds foreign newsreels of the Great War, including almost all of the French war newsreels, Les Annales de la Guerre.

BRITISH PATHÉ:

Under the heading The Complete WW1 Collection, British Pathé has compiled a large collection of World War I footage arranged by subject and geographical criteria. The collection consists of archive footage, often provided with only a rudimentary documentation. Therefore, it is not clear which film documents were published during the war and whether they were used for the production of newsreels.

BUNDESARCHIV (FEDERAL ARCHIVES):

Only a part of the German newsreels produced during World War I has been preserved. The surviving issues of Messter-Woche, Eiko-Woche and newsreels published by smaller companies are stored at the Federal Archives. Within the framework of the EFG1914 project, only about a dozen issues have been digitized. These newsreels as well as documentary films, produced by the Bild- und Filmamt (Bufa) and digitized for EFG 1914 project, are also available via the film portal of the Federal Archives.

CNC Patrimoine – Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée:

CNC Patrimoine offers a central access to France’s contributions to the EFG1914 project: films from the Archives françaises du film du CNC, the French Army Picture Agency ECPAD and the Archives des Musées Albert-Kahn. The selection contains approximately 140 titles which, besides documentar films, include some editions of the war newsreel Les Annales de la Guerre.

ECPAD/Agence d’images de l’armée :

The picture agency of the ECPAD (Établissement de Communication et de Production Audiovisuelle de la Défense) documents the First World War on the basis of documentary films and about 20 issues of Les Annales de la guerre. ECPAD is the official Audiovisual Communication and Production Office of the French Army.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES / NARA:

U.S. Signal Corps footage of the Great War is preserved at the National Archives and Records Administration. Films are linked to original paper documents containing information about the content, time and place where the footage was taken. The available films mainly consist of documents edited after the war. From the film documents, it is not clear what part of the footage was published during the war, or was shown to the public in newsreels.

No issues of the weekly war newsreel Official War Review, distributed by Pathé for the CPI, is available on the portal of the National Archives. Apparantly, there are onliy a few issues preserved and they are difficult to trace. The National Archves has created a compilation containing 6 issues the Official War Review. It was shown in 2015 at the Silent Film Festival organised by the Cineteca del Friuli and on that occasion uploaded to the Web: Official War Review (USA 1918 /1919).

The National Archives hold the most important stock of films and footage of the Great War in the United States. The documents are preserved mainly in 4 major collectens: U.S. Army Signal Corps Historical Collection, CBS World War I Collection, Ford Film Collection, and the Durborough War Pictures, containing original footage taken by Wilbur H. Durborough, an American press photographer.

In the framework of a National Archives project (2014-2018), the holdings of the U.S. Army Signal Corps Historical Collection were partly repaired and re-digitized in high resolution. A wide selection of films is now available on the YouTube channel of the National Archives. This considerably facilitates access to the film documents and thus makes them accessible to the general public.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES’ Youtube Channel:

On the National Archives’ YouTube channel, an extensive selection of U.S. Signal Corps films related to World War I is available. This makes access to the films much easier und thus opens the treasures of the archives to a broad public.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS / On the Firing Line With the Germans: h

Documentary film by W.H. Durborough and the cameraman Irving Ries. In 1915, they spent seven months in the German Reich where they documented everyday life und the German offensive in the East, in Poland and Russia. German authorities, at this point in time, were eager to make their view of the war known in the USA. The film was successfully shown in many theaters in the United States in 1915 and 1916. Although not a newsreel, the film is instructive for this article’s topic.

On the Firing Line With the Germans was recently restored by the Library of Congress in collaboration with the National Archives, based on the footage contained in the Durborough War Pictures archive.

All newsreels linked to in the article (in the order of their appearance in the text):

L’offensive française sur la Somme

Bei unseren Helden an der Somme

Les Spahis algériens en Belgique

La Main d’oeuvre féminine dans les usines de guerre

Pictorial News (Official) 345-2

Les Annales de la guerre No. 37

Les Annales de la guerre No. 27

Im Lazarett Aßfeld in Sedan 1917

Les Annales de la guerre No. 66

L’Avance française des Soissons à Reims

Wie Frankreich das Elsass befreit 1917

The St. Mihiel Offensive, Sept. 10 to November 25: (National Archives YouTube Channel)

The St. Mihiel Offensive, Sept. 10 to November 25: (National Archives Website)

Meuse-Argonne Offensive, September 26 to November 11, 1918 (National Archives YouTube Channel)

Meuse-Argonne Offensive, September 26 to November 11, 1918 (National Archives Website)

Mobilizing Movies! The U.S. Signal Corps Goes to War, 1917-1919